As the father of three teenagers, as a son whose father lost his battle with cancer, and as a physician-scientist who specialized in cancer research for more than four decades, I was heartened by the recent and welcome news of continued declines in US cancer mortality rates, driven by continued reductions in tobacco use, increased early detection strategies, and the development of immune therapies.

Even sharper declines can be realized by implementing more aggressive and comprehensive proven cancer prevention and control strategies.

Up to half of cancers are preventable — they never have to occur. While cancer typically afflicts older individuals, most of cancer’s instigators plant their seeds during childhood. That means decisive action early in life can prevent cancer-related suffering and death for countless individuals as adults.

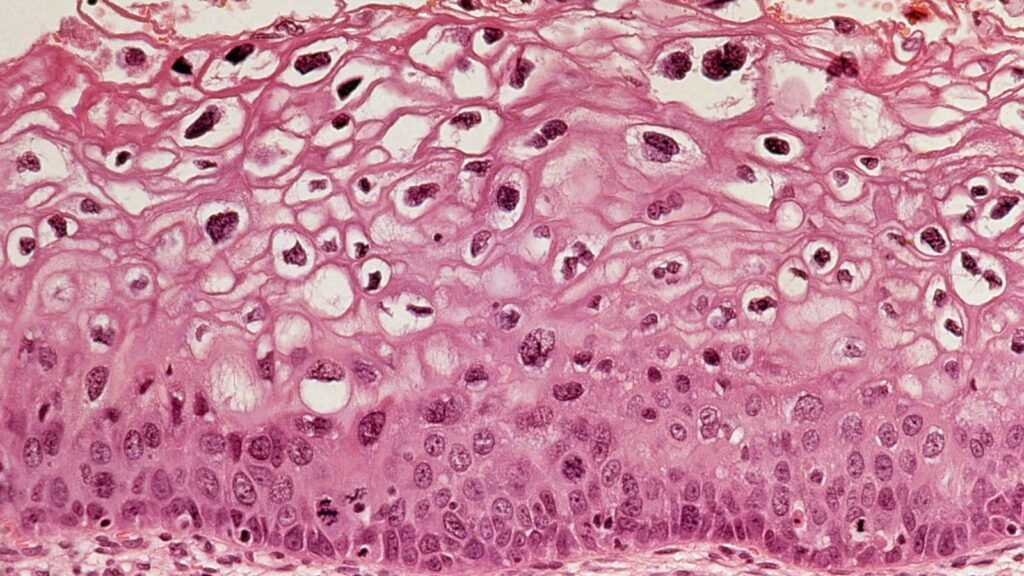

This fact, combined with emerging information about a preventive strategy against the human papillomavirus (HPV), creates a potential game changer in the fight against cancer. HPV, the most common sexually transmitted infection, can cause several cancers: cervical cancer in women, penile cancer in men, as well as some throat, anal, and other cancers. In the U.S., the number of cancer cases linked to HPV have soared by nearly 45% over the past 15 years.

In 2006, the FDA approved a safe and effective HPV vaccine that, when administered between the ages of 11 and 26, can prevent almost 90% of HPV-related cancers. (The vaccine produces the strongest immune response in 11- and 12-year-olds, before they are exposed to the virus). The vaccine currently requires two doses, with the second given six to 12 months after the first. Unvaccinated men and women ages 27 to 45 can also get the HPV vaccine and should consult with their physician about the benefits given their individual health needs.

Evidence from a soon-to-be-published 11-year update of the Phase 3 Costa Rica HPV Vaccine Trial, co-led by investigators from Costa Rica’s Agency for Biomedical Investigation (ACIB) and the U.S. National Cancer Institute, is signaling that the protection provided by a single dose of the HPV vaccine may be as durable as protection from the two-dose series. This is very important. If a one-and-done vaccine regimen can achieve the same goal as the currently recommended two-shot series for adolescents, vaccination rates would improve, the global burden of cervical and other cancers would substantially decrease, and vaccination and administrative costs would be dramatically reduced.

Thanks to Nobel Prize-winning science, we know that millions of cancers — up to 15% of all new cancer cases each year — can be prevented from ever starting by eliminating infectious agents responsible for them. HPV alone, which affects nearly all adults in their lifetimes, causes one-third of these preventable cancers.

The body’s immune system usually clears out an HPV infection. But the virus persists in some people, causing HPV-related cancers in more than 600,000 men and women worldwide each year, the majority of them (85%) in low- and middle-income countries where cancer treatment is suboptimal or nonexistent. In these low-resource settings, cancer prevention may be the best option to save lives.

Two models presented in The Lancet suggest that over the next 100 years, more than 74 million cases of cervical cancer and 60 million deaths from it could be averted through HPV vaccination, and the disease could be eliminated in the 78 countries bearing the highest burden of the disease.

The development of a safe and effective vaccine that reduces the odds of getting HPV-related cancer later in life represents a tremendous advance. Regrettably, it isn’t being used to its full potential. Misinformation, such as the vaccine will promote sexual promiscuity (disproved in a large study), unfounded safety concerns, and other barriers to HPV vaccination are keeping the world’s youth at risk for these unnecessary and painful cancers later in life.

The good news is that while different challenges regarding HPV vaccination exist in the U.S. and low- and middle-income countries, they are highly solvable.

Fewer than half of American adolescents have been fully vaccinated against HPV, far short of the 80% goal officials set for 2020. Vaccine uptake is low due to a variety of reasons, but the ones most frequently cited by parents are that they didn’t receive a physician’s strong recommendation for vaccination or they lacked knowledge or needed more information about the vaccine. In addition, more than half of adolescents who start the HPV vaccine series don’t complete the currently recommended 2-dose vaccination protocol.

In low-and middle-income countries, the challenges relate mainly to inadequate vaccine supplies. HPV vaccine production is projected to remain insufficient to meet global demand until at least 2024.

A single shot for life coupled with educating clinicians and providing them with incentives to more positively and assertively recommend the HPV vaccine would catapult the U.S. towards its goal of 80% vaccinated. Why 80%? At this level of vaccination, it is difficult for the virus to spread in a population, providing what is known as herd immunity that helps protect even those who have not been vaccinated, essentially eradicating HPV-related cancers for the next generation. According to a CDC study, vaccination rates among early adolescents are greater than 75% with providers who proactively recommend the vaccine, compared to under 50% with providers who are more passive in their recommendations.

The cost of inaction is high. In the U.S. alone, vaccinating all 11-year-olds with the current two-shot regimen would cost approximately $1.3 billion per year compared with $8 billion per year to treat more than 34,000 HPV-related cancers.

There is little reason why parents and providers should not be vaccinating every child against HPV, especially if one dose turns out to be enough. We need to do better at protecting our children from cancers they never need to get.