As our nation experiences the initial peak and abatement of Covid-19 infections and deaths, many will reflect on what we could have done better and how we could have acted sooner. It is clear Covid-19 will be an event that will reshape society in lasting ways. As we look to the future, we can anticipate continual waves of innovation across multiple platforms including effective testing, digital health, anti-viral medicines and ultimately vaccines. If all goes well, America’s nightmare will be over, right?

Perhaps, but only if we anticipate and take proactive measures now to address what could be an even greater societal and medical problem. Following Covid-19’s infection of the lung and resultant inflammation and pneumonia, a significant fraction of survivors will sustain a condition, known as pulmonary fibrosis (lung scarring). Pulmonary fibrosis has the potential to create lasting disabilities and ultimately extract more lives than the entire acute phase of this pandemic.

Let’s not get caught flatfooted, again.

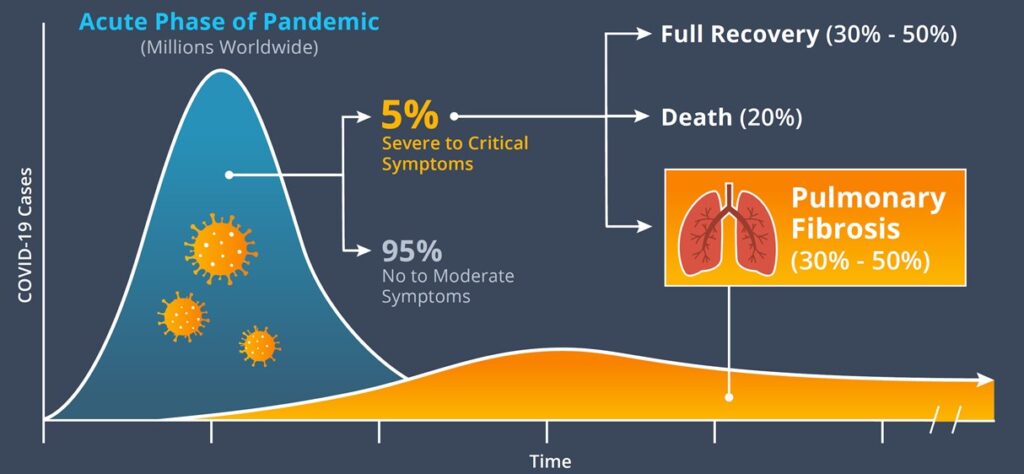

At this moment, we have an opportunity to proactively unleash the power of American science on the gathering storm that will soon confront us – the long term effects from Covid-19. Thanks to our national mitigation efforts, conservative models predict that only tens of millions of Americans (hundreds of millions worldwide) will ultimately be infected by the Covid-19 virus before a vaccine becomes available in 2021. The vast majority of people will experience no to moderate symptoms and recover fully, while up to 15% will experience severe to critical illness, ending in one of three ways: – approximately one quarter will die, one quarter will recover fully and nearly half will develop long-term lung scarring (pulmonary fibrosis) with diminished lung function. The impact on quality of life for survivors would be immeasurable.

Reviewing data from the highly related SARS-CoV in 2003, reveals that 36% to 62% of survivors experienced sustained pulmonary fibrosis and diminished lung function. Given the similarities of SARS-CoV and Covid-19 viruses and the body’s response to them, we can anticipate that, by the end of the pandemic, many thousands of Americans who have survived severe cases of Covid-19 will be left to deal with lingering effects of the virus and crippling pulmonary fibrosis which may require supplemental oxygen, ventilator support, and possibly even lung transplantation.

The pulmonary fibrosis and diminished lung function seen following SARS, and anticipated following Covid-19, strongly resembles Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF), a lung disease characterized by low-grade pulmonary inflammation and progressive fibrosis. While we cannot extrapolate with certainty that Covid-19 pulmonary fibrosis and IPF diseases are identical, it is concerning that the majority of IPF patients succumb to respiratory failure within 2-3 years. The approved therapies for IPF are pirfenidone and nintedanib, which delay disease progression in only ~15% of patients. Lung transplant remains the only cure for IPF. Currently, there are 160,000 IPF patients in the US. Assuming a similar mortality rate to IPF, it is possible that the death and disability from Covid-19-related chronic lung disease could be several-fold the expected 50,000 to 100,000 deaths from acute Covid-19 infection.

The potential magnitude of this looming problem is of great societal and economic concern. As treatment options for pulmonary fibrosis are limited, our nation must anticipate and mount a call-to-action now to expedite the development of novel therapies to prepare for the next inevitable wave of disease stemming from Covid-19. Let’s get a running start as we wish we had with testing and anti-virals a few months ago.